PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — The Code of Hammurabi. The Magna Carta. The Declaration of Independence. Throughout recorded human history, written records such as these have proclaimed that people deserve freedom, security and dignity.

Why, despite huge cultural differences across continents and sweeping societal changes across centuries, have the underlying concepts in these declarations of rights remained largely unchanged?

According to a pair of scientists at Brown University, it’s because all humans share the same nervous system.

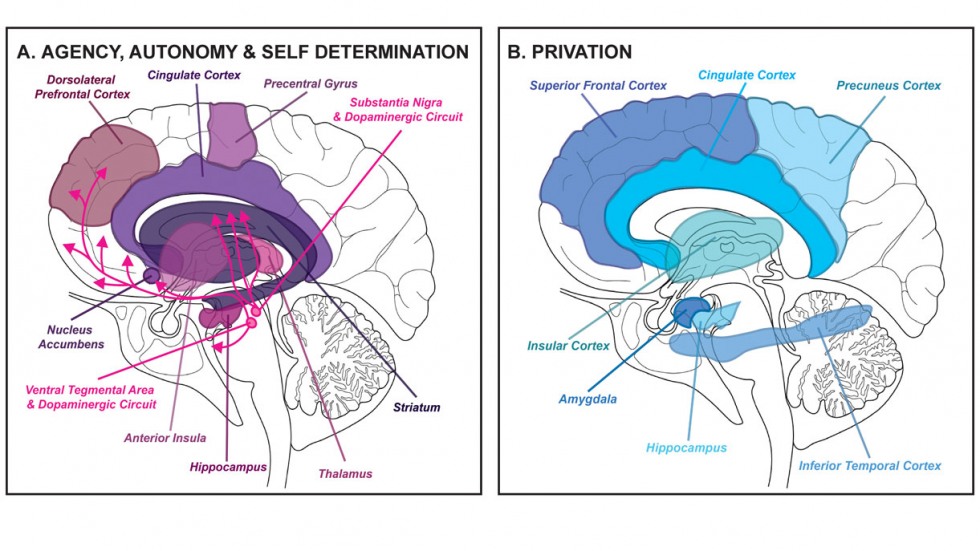

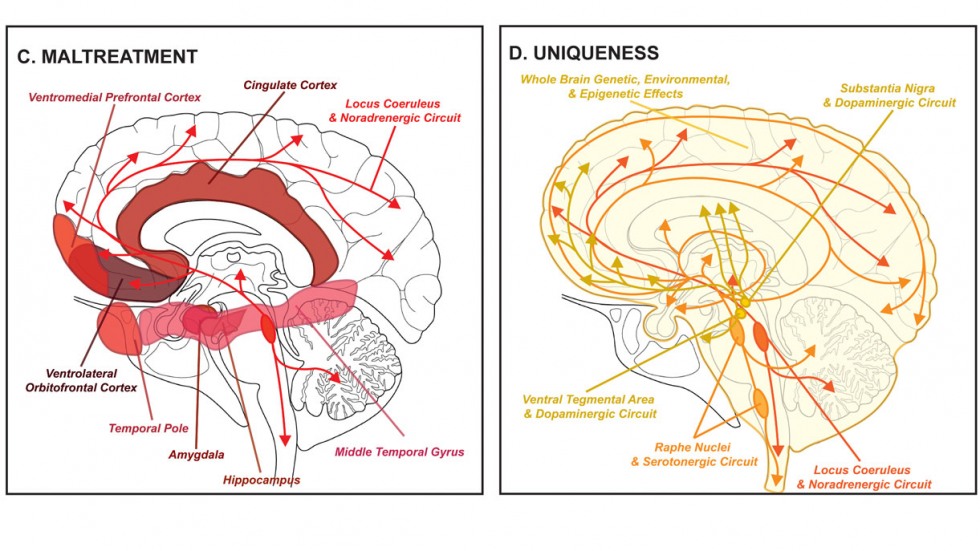

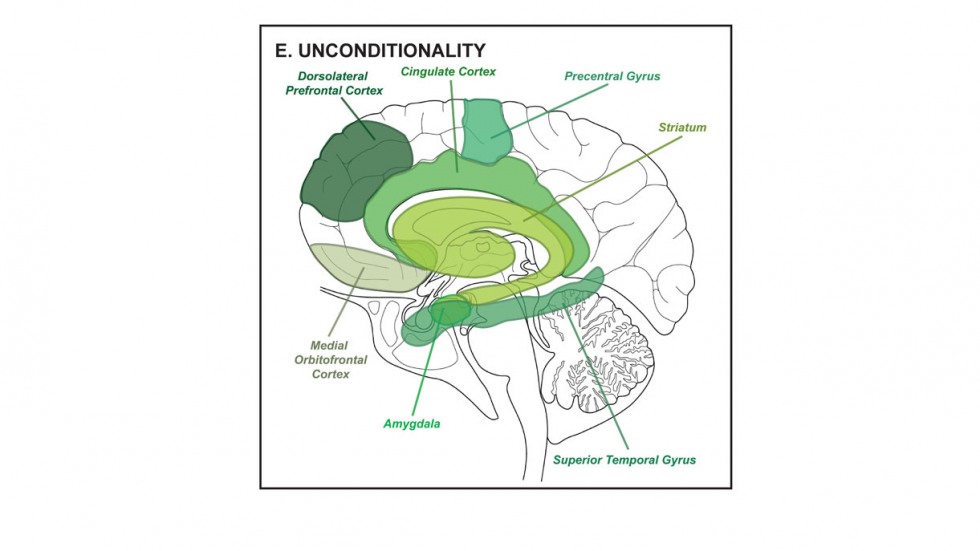

In a new scientific paper, the scholars introduce a new concept called “dignity neuroscience” — the idea that universal rights are rooted in human brain science. The authors argue that numerous studies in disciplines such as developmental psychology and neuroscience bolster long-held notions that people thrive when they enjoy basic rights such as agency, self-determination, freedom from want or fear, and freedom of expression. And they say science also supports the idea that when societies fail to offer their citizens such rights, allowing them to fall into poverty, privation, violence and war, there can be lasting neurological and psychological consequences.

The paper was published on Thursday, Aug. 5, in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

Tara White, the paper’s lead author and an assistant professor (research) of behavioral and social sciences at Brown, said she believes grounding universal human rights in science could help people see themselves in the sweeping statements of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“I think the average person on the street sees universal human rights as an international law concept that has more to do with trade than about individual lives,” White said. “But this stuff is not pie-in-the-sky, and it affects us all. We want to show people that ensuring universal human rights is a crucial foundation for a society that is healthy — not only socially and physically, but also psychologically and neurologically.”