PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Thanks to the work of one Ph.D. student at Brown University, high school students across the country are studying political cartoons to better understand the American zeitgeist early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Developed by Michael Dorney, a doctoral student in history, “Processing the Pandemic: Remembering a Year of COVID-19 through Political Cartoons” is a lesson plan that helps high school students explore, remember and process the first year of a life-altering public health crisis through political cartoons published in 2020 and 2021.

For centuries, Dorney said, cartoonists have harnessed the expressive power of illustration to explain complex ideas when words fall short.

“The cartoon appears to be a medium that’s very useful at getting across some tough ideas that we can’t quite put into words,” he said. “Cartoons have been around for a long time, and they can serve as a societal barometer: they allow you to immerse yourself in a specific place and time.”

The lesson is freely available to download through the Brown-based Choices Program — a program affiliated with Brown’s Department of History in which scholars collaborate to create high-quality history curricula for K-12 schools, many of which are available to teachers and school districts for free.

With Dorney’s lesson plan, teachers can use cartoons to help students understand what Americans were thinking and feeling as the novel coronavirus began to spread across the country, providing a window into the many ways in which the pandemic upended society, politics, the economy and the environment in the U.S.

The plan encourages teachers to lead small groups of students in exercises that help them recognize common cartoonists’ techniques, such as symbolism, analogy, irony and exaggeration, by studying real cartoons published during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students later come together to share their insights and discuss how political cartoonists shape social and political views. Optional challenges include cartoon annotation exercises and the opportunity for students to draw their own political cartoons using the techniques they learned about.

“I think this is a powerful way to study the pandemic,” Dorney said. “Sure, teachers could just assign students some reading about the anxiety levels of parents during the pandemic. But that might not drive the idea home in the same way as a cartoon showing parents sending their kids off to school in hazmat suits. It has students reflecting on their personal experiences — like, ‘yeah, some days it does feel like I’m basically wearing a hazmat suit,’ or, ‘my parents really do look scared when I go to school.’”

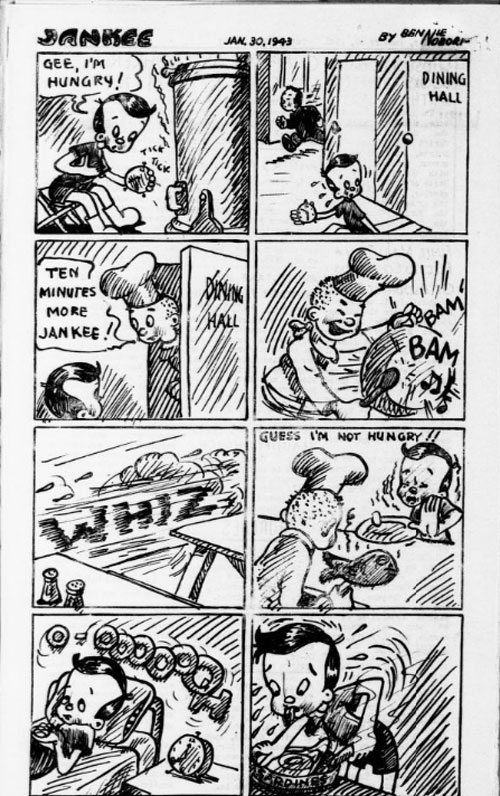

The history student developed an interest in cartoons somewhat accidentally. As part of a larger Ph.D. project that aims to shed light on the realities of the unjust imprisonment of more than 127,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans in the U.S. during World War II, Dorney is reading and analyzing newspapers that were written and printed by prisoners of Japanese descent from within internment camps across the country.

Dorney, who is a quarter Japanese, was intrigued to see that several of those newspapers — including the Topaz Times, printed by prisoners at the Central Utah Relocation Center — featured cartoons.

“What became apparent to me is that cartoons were an ideal method of communication in this setting,” he said. “Cartoons can carry multiple messages, some of which might have escaped the notice of the government censors who were put in charge of regulating the newspapers.”

Some cartoonists, for instance, were able to dodge censorship by simply concluding on a positive note. Cartoon strips would often fearlessly address the everyday struggles of incarcerated life, such as enduring long days of manual labor or eating subpar meals in the cafeteria — but they would conceal sentiments of resistance with messages about the importance of resilience and fortitude.

“That high note at the end, that sense of general optimism, gave cartoonists room to capture the everyday challenges in a way that didn’t look critical of the U.S. government,” Dorney said. “A camp administrator might think, ‘Oh, they’re having fun, they’re making light of their situation.’ But for the incarcerated, it was an opportunity to represent their experiences, to chronicle their lives, so that their stories wouldn’t be lost to time or silenced in the record.”

Dorney, who aspires to teach and conduct research in a university setting, noted that creating a Choices Program lesson plan gave him valuable experience designing classroom-ready lessons.

“My work with the Choices Program has been great at exposing me to different types of pedagogical styles and strategies,” Dorney said. “It’s very useful for me, as someone who is pursuing a career in academia, to find creative ways to simplify complex ideas.”

The work also allowed Dorney to draw connections between his dissertation research and current events in the U.S. Namely, he said, it’s driven home one timeless truth: That cartoons can provide a much-needed emotional release in difficult times.

“Humor can somehow be both an expression of pain and a mechanism for coping with pain,” Dorney said. “It allows us to process tough topics and begin to move on. The pandemic is an event that, like 9/11 for my generation, like the fall of the Berlin Wall for Generation X, is going to linger in current high school students’ memories for a long time. So they might find some catharsis in studying these cartoons and retracing the gradual national shift from despair to hope.”