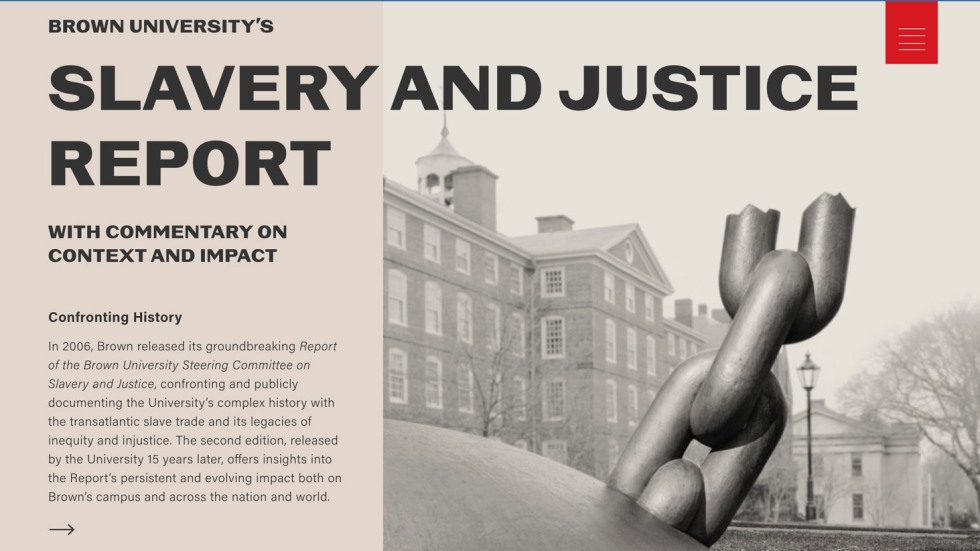

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Fifteen years after publishing a groundbreaking report on its own historical ties to the transatlantic slave trade, Brown University has released an expanded second edition of the report amid renewed national conversation on slavery’s legacy.

With new insights on the original text’s national and local impact, the new edition of the Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice offers an unflinching assessment of how far Brown has come in implementing the report’s original recommendations and what remains to be accomplished.

In a foreword to the second edition, Brown President Christina H. Paxson wrote that the expanded report comes in the context of a long-overdue reckoning with the terrible legacies of anti-Black racism. In 2020, millions watched in horror as police violence, and the COVID-19 pandemic, claimed a disproportionate percentage of Black lives — realities that shed light on the indelible connections between historical slavery, anti-Black racism and systemic inequality.

“It is through the lens of these complex issues, inextricably intertwined with the legacies of slavery, that we revisit the Slavery and Justice Report,” Paxson wrote. “American society in the 21st century demands that institutions of higher education continue to evolve and respond to the complex world in which we live as we interpret our past. It is for these reasons that we are publishing this second edition of the report.”

Published on Friday, Nov. 12, the second edition of the report is available through an immersive, interactive digital experience and as a printed book. Both versions include the report’s original text along with reflections and commentary from Paxson, President Emerita Ruth J. Simmons and Brown faculty, staff and alumni. A live-streamed event at Brown beginning at 3 p.m. on Friday will convene leaders from both the original and reimagined reports for a series of discussions.