First, it is important to cite and credit the critical frameworks and theories of change that inform our approach to violence prevention work as a whole and subsequently, action planning. As SAPEs, we believe in an intersectional, power-conscious approach to violence prevention.

“Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects.” - Kimberlé Crenshaw

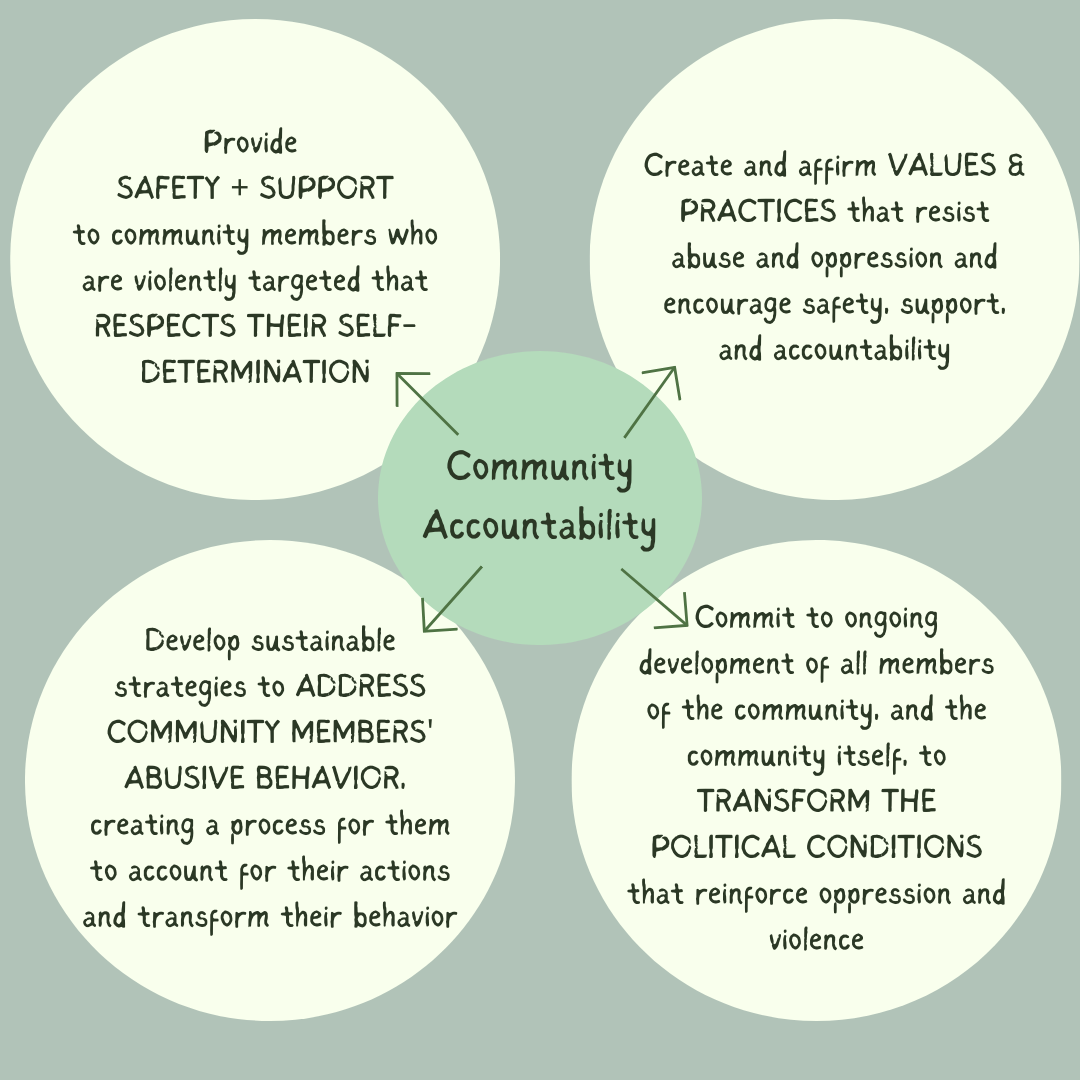

These frameworks urge us to understand the root of sexual violence as power and oppression. Power can be defined as “access to the ability to control or significantly influence other people’s lives.” (Linder, Sexual Violence on Campus, p.7) Systems of oppression create an environment where sexual violence is inextricable from the intersectional marginalized identities people hold around race, gender, class, ability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and caste (to name a few). For years, sexual violence has been framed as identity neutral, but we know that this notion is false and harmful, perpetuated by dominant voices in dialogue around sexual violence. The dominant assumptions about sexual violence have carefully constructed the image of a victim as a white, cisgender, heterosexual, college woman, relegating the experiences and knowledge of survivors of color, queer survivors, disabled survivors, immigrant or undocumented survivors, sex-worker survivors, and low-income survivors to the margins, despite disproportionately being targeted for sexual violence. If we are to create plans of action for eradicating sexual violence, it also means showing up for racial justice, economic justice, queer justice, disability justice, immigrant justice, etc. Understanding and acknowledging power, privilege, and dominance is inherent to understanding why sexual violence occurs. See below for related definitions and concepts.

Intersectionality: coined by Black feminist legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw, intersectionality describes how systems of oppression overlap and intersect for people holding multiple marginalized identities. She uses the term intersectionality to explain how looking at systems of oppression as separate structures for people with multiple marginalized identities fails to encapsulate the unique experience of both systems at the same time. (Crenshaw, Mapping the Margins)

Power-conscious approach: this framework focuses on “the relationship of people with power to systems of oppression” in order to “consider the role of power in individual, institutional, and cultural levels of interactions, policies, and practices.” Linder’s framework explicitly urges stakeholders to address sexual violence by dismantling structures of power and privilege rather than teaching victims to not be victimized. (Linder, Sexual Violence on Campus, p. 14). Taking a power-conscious approach means engaging in reflective, self-awareness work, considering history and context, making behavior changes based on our reflections, pointing out power imbalances and the role of power in structures and policies as well as in community and individual actions, and to work towards the eradication of all forms of oppression.