Mobility and Schooling in Cuba

Formal education and schooling have been central tenets in the quest for modernity and nationhood across postcolonial societies in the twentieth century, and schools have been harnessed to produce modern, national subjects. Yet education and schooling also foster and encourage aspirations of geographic mobility beyond national borders. In Cuba this tension has proven challenging for the socialist government. Education is widely seen as one of the most enduring and positive achievements of the revolution, so emigration of those educated in the socialist system has represented not only a loss of skilled personnel, but also a political embarrassment for the revolutionary government.

For a period of several years, I have tracked the transnational networks of alumni of the “V.I. Lenin Vocational School” (known as La Lenin), socialist Cuba’s most prestigious school. In all, I have conducted 50 interviews with alumni about their memories of schooling and what it means to them today. I talked to alumni ranging in ages from 19 to their early 50s, evenly split between men and women, and including pupils at the school between 1972 and 2010, currently living in Spain, Cuba, France, the US, and UK.

This research arose from a paradox, a puzzle that I kept encountering in my earlier research on the Cuban diaspora in Spain. From the very beginning, exit from socialist Cuba has been problematic for the revolutionary government, yet diasporic alumni of the Lenin School kept telling me how connected they feel to their old school and to other alumni. This manifests virtually in a plethora of social networking groups and a corpus of online poetry and music paying homage to the school. Offline, alumni maintain friendships, often transnationally, and some participate in regular alumni meetings. For many alumni, it is a fundamental part of their self-identification, suggesting an intimate link between schooling and sense of self. Strikingly, alumni often articulate their relationship to the school in the same way that others might talk about national identity. One woman summed it up neatly:

I would say that it is one of my passports, wherever I go, I always say that I am from La Lenin. I wouldn’t live off of it, I don’t go around saying it all the time…but I would easily say that it is my visa in a group of friends. At least it’s been like that, when I get to know a Cuban who wasn’t in my year group, I always ask: “Are you from La Lenin?” It’s something you need to ask to establish a conversation or to let off some steam outside Cuba.

(Claudia, interview in Barcelona, pupil at La Lenin in the late 1990s)

I suggest that the kind of informal network that Claudia and many others described to me can helpfully be seen as forming part of a diasporic public sphere: a non-nationalist diasporic formation.

Given the politicized nature of any recollections of Cuba, it is worth stating here that memories are never simply records of the past – we remember selectively and our memories are always embedded in the cultural and social contexts of recall. Accordingly, what I set out to do in my research was not to verify or document the relative merits or otherwise of Cuba’s educational system, but simply to explore why alumni of La Lenin continue to identify so strongly with their old school even when they have left Cuba, and what this tells us about belonging in Cuba and its diaspora.

The V.I. Lenin School and the New Man

La Lenin is an academically selective boarding school in Havana for 15- to 18-year-olds. It was founded in Havana in the early 1970s in order to create a new political subject, Ernesto Che Guevara’s Hombre Nuevo, or “New Man,” who would build socialism in Cuba. The compound of the Lenin School lies on the outskirts of Havana. In its heyday, the facilities included purpose-built accommodations and teaching facilities, a library, sports fields, Olympic-sized swimming pools, theaters, numerous fully equipped language and science labs, an infirmary, hairdressers, and a factory where the pupils were to work part-time. In the words of one alumna whose father had been among the first cohorts, it was “the dream of the revolution at that time.”

It was a flagship school with extraordinary status and resources allocated to it from the very beginning, speaking to the importance of education for the revolutionary government. Alumni from La Lenin who have subsequently left Cuba therefore by definition embody a failure of the revolutionary project, given the investment in the school – financial, political, and symbolic. Against that background, what is at stake when diasporic alumni continue to identify with the school and claim it as a site of belonging when they manifestly have not become the revolutionary subjects the school was meant to make them into?

I suggest that seeking answers to this question can help us elucidate aspects of Cuba’s recent history from the point of view of some of the subjects who were symbolically and materially privileged as the intended beneficiaries of the revolution. It can also tell us something about the nexus between social and spatial mobility. Several scales of mobility were important to my research subjects, ranging from the move from their local, neighborhood school to the prestigious and nationally recognized Lenin School, and later to university studies, sometimes abroad; but also the move from parental home to boarding school, and later international migration. For many of my interlocutors, their initial move from childhood home to boarding school, which was geographically small-scale, carried more significance and was seen as involving a bigger change in their lives than their later transnational mobility. Leaving the family home constituted a moment of growing up and becoming independent. Additionally, becoming a pupil at the school entailed the conferring of substantial social prestige, in some cases signifying the consolidation of elite status, and in others upward social mobility. In all cases, the school provided a transformational experience.

Diasporic subjects do not always identify first and foremost with their homeland in the way that labels such as “the Cuban diaspora” suggest. Instead, relationships to significant others and particular places such as home, street, neighborhood, city, or region can constitute more significant sites of belonging. In this case, the move to live and study at the Lenin School, and the social status being a pupil of the school entailed, appears more significant in the self-narrations of my interlocutors than their subsequent international mobility. A woman now living in New Jersey stated emphatically, “the school made me who I am,” and a man living in Mallorca called it “a legacy, like a brotherhood, it marks you.” While not all alumni feel so strongly about the school, for many it was a very significant part of their self-identification, suggesting an intimate link between schooling and sense of self.

In effect, the networks of school-based friendships and family relations – the two are increasingly intertwined as alumni intermarry, and recent graduates often represent the second generation in their family to attend the school – constitute a transnational affective geography of belonging, produced and reproduced through memories, narratives, reciprocal support, and embodied performances of alumni identity. How did this come about?

The revolutionary government aimed to create a new political subject, the Hombre Nuevo, or New Man, who was to be a socialist and a patriot. For Ernesto Che Guevara, forging the Hombre Nuevo was as important for constructing communism as the transformation of the material base of Cuban society. Schools explicitly aimed to minimize the perceived pernicious influence of tradition in families: instead, the new Cubans were to be children of the revolution.

Without access to the school archives, the degree of social mobility the new system entailed is difficult to establish. An account from the late 1970s suggests that by then, the school had achieved gender equality in its enrollment. From interviews and testimonies of alumni it is evident that the vast majority of pupils at the school historically and at present are “white” [blanca/o], reflecting longstanding problems of racialized inequality in Cuba. In terms of socioeconomic background, a man now living in New Jersey suggested a mixed picture:

There were definitely people from poorer backgrounds and from the middle classes, but the people from the upper class never missed [being admitted]…I entered in…1972…The children of Fidel [Castro] studied in my year, three of them; Che [Guevara’s] daughter…the children of all the ministers [and] important personalities…Between all of them were the rest of us who didn’t come from powerful families.

The accounts of life at La Lenin by alumni are surprisingly consistent despite the up to forty years separating their time at the school. They describe a daily life entirely contained within the school compound, consisting of strictly regimented days starting with wake-up calls on the central tannoy at 6 a.m., followed by morning exercises, inspection, breakfast, and classes. Most students were required to participate in manual labor two to three afternoons every week. The evenings were dedicated to independent study with one evening a week set aside for entertainment organized by the school. Pupils would usually go home every weekend, although this right might be taken away as punishment for disciplinary infringements.

Legacies of School Life

Could it be that the Revolution was so successful in socializing its children and young people that the friendships made at boarding schools came to be more important than family and politics? Could this explain the strong attachment to schools such as La Lenin, even when its ideological framework is partly or wholly rejected? Time and again, alumni recounted stories of friendships that had endured beyond the school years. This is what Andris, who studied at La Lenin in the 1990s, but now lives in Spain, said about the legacy of the friendships he made at the school:

[My friends] are almost all from La Lenin…some of them are friends from university but they also went to La Lenin...They organized a party for me when I arrived [in Barcelona]. It was more like moving from one neighborhood to the next, I was already well integrated when I arrived here…I really enjoy living here…I miss my parents, but I don’t really miss Cuba. Basically what one misses isn’t that bit of land anyway, it’s the people and they’re not there anyway…my generation is all outside of Cuba.

Concluding Thoughts

The Lenin School is one part of the history of revolutionary Cuba, told here as experienced by some of the subjects who were central to revolutionary understandings of subjecthood. One of the paradoxical and clearly unintended consequences of the school was to forge strong affective bonds between alumni, not only among those who spent time together at the school, but more broadly between all alumni – a kind of imagined community, a term coined to describe national belonging. Yet the transnational networks I have described here are an example of school-based associations, which create diasporic sociality not based on nationalism or national belonging but through a school and shared experiences at a formative age: a diasporic public sphere in which the nation-state is not the key arbiter of social changes.

This raises questions about to what extent an identification with La Lenin is also an identification with Cuba as a nation, and to what extent it is a non-national identification. Could we see school networks as a kind of anti-essentialist, anti-nationalist diaspora formation? These issues are important because they raise wider questions about the potential for diaspora contribution to homeland development and about belonging and diaspora formation in a context of globalization and transnational migration of the elite/highly skilled.

Finally, the testimonies raise questions about the nexus between social and spatial mobility and their cultural and social significance for mobile subjects in a globalizing world. It would seem that scholars of migration are guilty of over-determining their object of study, i.e. “migration,” when in some contexts, we might be better off starting with people’s life worlds and then asking about the significance of migration.

This article is based on a longer piece: “‘La Lenin is my passport’: schooling, mobility and belonging in socialist Cuba and its diaspora,” published in Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power [paywall]. All interviews were conducted in Spanish; names of interviewees have been changed to protect anonymity. I am grateful to the John Fell OUP Fund for funding, to Margalida Mulet Pascual for research assistance, and to all alumni for their generosity in sharing their experiences with me. All errors and inaccuracies remain mine.

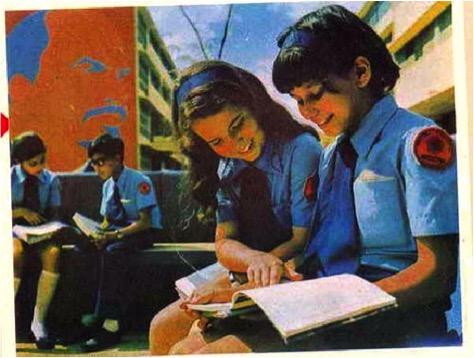

Photo Credit: Author's personal collection, provenance unknown.