Haitians’ Daily Lives in Cuba

At first blush, the Haitian sugar workers who migrated to eastern Cuba in the first three decades of the 20th century are not good candidates for challenging the “sugar curtain” framework. In some ways, they built it. Throughout the republican period, Cuban writers spanning genres and political perspectives understood Haitian labor migration as a byproduct of a US imperial rule bent on ensuring sugar production at any cost. As third parties brought in to cut cane, Haitian migrants were alienated in the eastern Cuban enclaves where they lived—seeming proof of sugar’s power. In fact, a close look at Haitians’ daily lives and experiences challenges all of this. It allows a more nuanced understanding of the contours of the sugar industry and how communities actually experienced life on a plantation. They are a reminder that efforts to demystify metaphorical sugar curtains may be achieved, not simply by holding them aside, but also by adjusting our eyes to the light and recognizing what lies beyond their translucence.

If the image of a “sugar curtain” implied separation between the United States and Cuba after 1959, sugar was a source of economic connection in the preceding half century. During the first decades of the twentieth century, sugar was the most valuable economic sector in Cuba; the island was one of the world’s largest producers. “Without sugar, there is no country” went the popular refrain—and it seemed like everyone knew it. During the various political rebellions that characterized Plattist Cuba, activists and political rebels knew that success could hinge on their ability to control valuable sugar mills and leverage the safety of company infrastructure for their own political goals.

The capital that sustained that industry was foreign and the labor force was largely immigrant. Before the era of mass deportations in the 1930s, some 200,000 Haitians traveled to Cuba—both seasonally and permanently. The Haitian migrants who labored on plantations were chided as pawns of sugar companies and anathema to Cuban national development. A host of writers, journalists and social scientists claimed that Haitians were a threat to public health, political stability, the Cuban labor movement, black Cubans’ efforts to secure full citizenship, and Cuba’s march toward a civilized future. The fact that the first laws allowing this contract migration were unilaterally decreed by the Cuban president after pressure from sugar companies and opposition from others only cemented the sense that Haitians were an imperial imposition.

Across the Windward Passage, US imperialism proceeded apace. In 1915, US Marines invaded Haiti, took over the government, imposed a new constitution, and aligned the country’s political economy with US regional interests. The peak flows of Haitian migration to Cuba occurred during these nineteen years of US occupation.

The circular movement of Haitians to Cuba was only one part of a hemispheric process in which the US military, American investors, and migrant laborers transformed societies in the period before the Great Depression. US Marines were deployed in Panama, Nicaragua, Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic in short and long occupations. Banking interests and capital investments were never far behind—in those cases in which they weren’t already there. In Cuba, Haitians were joined by smaller but still significant numbers of other immigrants from elsewhere in the Caribbean, with an especially large number from English-speaking islands like Jamaica. British Caribbean immigrants also migrated to work on other US projects like Central American banana plantations and the construction of the Panama canal. Migrant laborers from various Caribbean locales worked on US-owned farms in the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Hawai’i. If migration was a defining feature of world history in the early twentieth century, the Caribbean variant of that story is inseparable from the realities of US capital expansion and its labor needs.

From the vantage point of the sky, it looked like an imperial division of labor that shuffled Caribbean workers according to the labor needs of US companies. Some islands sent migrant laborers, others brought them in to work on the new sites of investments. But people do not live in the sky and things were very different on the ground. As renowned anthropologist Sidney Mintz explained, if the layout of sugar mills, cane fields and “workers’ shacks” had a certain “picturesqueness” from above, “walking through a village destroys such impressions.” (Mintz, Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History, Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishers [1960], 1974, 12). It is possible to take his observation even further. Following Haitian migrant laborers as they moved in and out of the Cuban sugar industry requires us to reconsider the power of sugar and empire in Cuban daily life.

It is an oversimplification to attribute Haitian migration entirely to the policies of the US imperial state or the demands of sugar capital. Small groups of Haitians and Cubans had moved between the two countries throughout the century before a Cuban presidential decree legalized migration in 1913. A sizeable number of Cubans settled in Haitian cities during the Cuban independence wars from Spain in the late 1800s. Haitians traveled to Cuba as well. Immigration statistics are unreliable or unavailable before legalization but Haitians are prevalent in Cuban official documents like citizenship applications, marriage licenses, and police records. Haitians were in Cuba before 1913, even if they were not being counted upon arrival. In short, the expansion of US capital, the Cuban legalization of migration and the US occupation of Haiti expanded and institutionalized a pre-existing flow of people; they did not cause that flow. Obsessing about sugar and the imperial state can obscure as much as it reveals.

Furthermore, sugar companies did not dominate the lives of their workers to the extent that it is normally assumed. One of the most commonly repeated characteristics of sugar plantations was that they segregated workers by nationality and race—a technique that dates back to slavery. There is a lot of evidence in other Caribbean settings to suggest that these company techniques generally promote racism among workers themselves. Sugar administrators certainly sought to implement this. Had they been successful, it would have represented a case where the US-Cuban sugar complex extended its influence into the social relationships among workers who were neither Cuban nor American. But in actuality plantation life never functioned in this way, despite managerial claims to the contrary. This is evidenced by records produced by sugar firms themselves. Companies were required to file accident reports when a laborer became injured; a study of these shows workers from different nationalities working together in various parts of the sugar production process. Racial segregation may have been the goal but it was not achieved on the ground. This has ramifications for the way we think about social relationships and interactions across racial lines as well.

In the hours and spaces outside of work, there was even more interaction among workers of different nationalities. Consider the case of the Haitian migrant worker named Ney Louis Charles. He was living and working on the US-owned United Fruit Company plantation in 1919. One evening, he was performing Haitian songs on his violin and taking song requests (in English) from an unnamed Jamaican woman. Some claimed that she was his girlfriend, others suggested that she was a prostitute. Whatever the case, a Cuban rural guard was also in love with the woman. This was only one snapshot, from one evening, on one plantation but the interactions across national lines are clear. These and other activities occurred nightly on plantations throughout Cuba without leaving a large trace in the historical record. Haitians, Cubans and other immigrants shared food, gambled, had sex and created communities on plantations that defied conventional understandings about worker segregation and the racism it creates. The reason we have a glimpse of this particular evening is that the Cuban rural guard killed Ney Louis Charles in a fit of jealousy and the story was investigated by a Haitian writer (Lélio Laville, La traite des nègres au xxème siècle ou l’émigration haitienne à Cuba, Port-au-Prince: Imprimerie Nouvelle, 1932, 8-10). In court records throughout eastern Cuba, there are rich descriptions of daily life that linger in the background of the exceptional details of criminal investigations. By compiling small snapshots from scattered and unlikely places, a world comes into relief that challenges the narrative of sugar’s unrivaled dominance in Cuban society.

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of race, imperialism, and sugar in Caribbean history, but even many critics have exaggerated their power in early twentieth-century Cuba. Among them were journalists and company officials who depicted Haitians in monolithic terms as powerless and isolated. Their inaccurate renderings of Haitians did not stop people from consuming newspapers and sugar, even if they did warp the historical record. The first step in understanding Haitians’ lived experiences is interrogating the assumptions that inhere in this Cuban print culture. As a result, reconstructing the actions of those deemed powerless are a stark reminder of the limitations on the powerful. From the life stories of Haitians it becomes clear: the sugar curtain is translucent and torn.

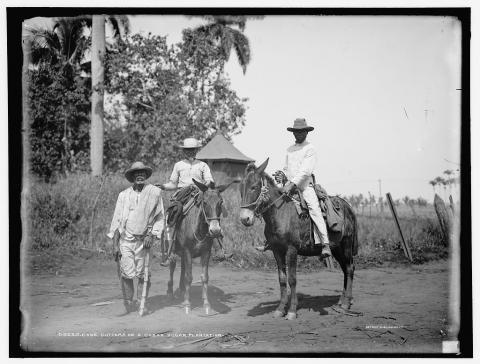

Photo: “Cane cutters on a Cuban sugar plantation,” Detroit Publishing Co., ca. 1900-1906, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.